EBRD-SRSS STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISE Restructuring Project

As discussed, many SOEs in Croatia are unprofitable and in need of financial and/or operational restructuring. Yet there is a clear lack of skills and experience at both the state and SOE-management level to effectively tackle financial difficulties and/or operational underperformance.

In response, the EBRD and the European Commission’s Strategic Reform Support Service (SRSS) launched, at the beginning of 2019, an EU-funded project for the Ministry for State Assets, and the Restructuring and Sale Centre (CERP) as beneficiaries. The purpose of the SOE Restructuring Project, as it is known, is to support the Ministry and CERP, as well as SOE management, in dealing with financially distressed SOEs. The Ministry manages, together with relevant line ministries, SOEs that are considered to be of special interest to the state and it is responsible for 39 of these companies. All other 374 SOEs (of which 25 are majority owned by the government) fall within the domain of CERP.

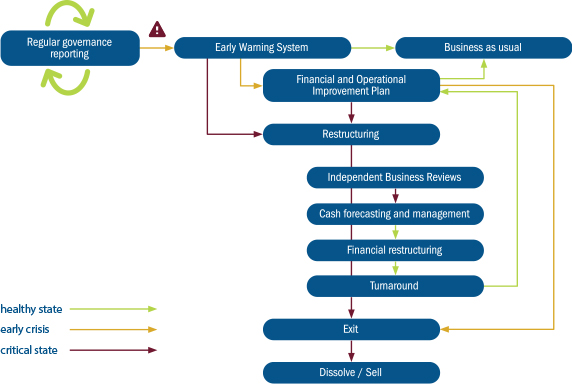

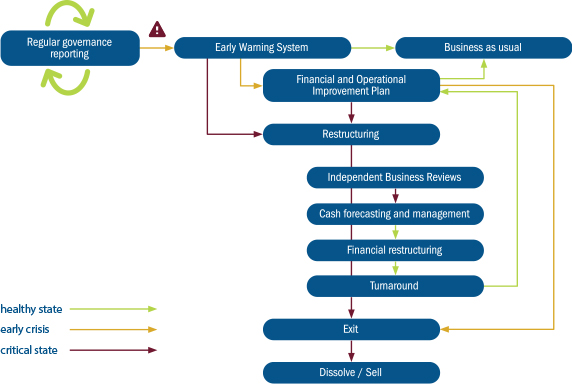

The SOE Restructuring Project, which concluded at the beginning of February 2020 with a workshop for government official and SOE management officials, has developed a comprehensive framework for preparing and implementing so-called financial and operational improvement plans (FOPIPs), as well as restructuring plans by the Croatian state bodies and the SOEs.

A FOPIP looks at what issues a business is facing, and the operational and financial impact of addressing those issues, and sets out how to transition to the business’s required future state, including the costs of achieving this transition.

In contrast, a restructuring plan is a more elaborate exercise and covers the following four elements:

- an independent business review

- cash forecasting and management, since the business is usually facing a short-term cash shortfall

- financial restructuring to address liquidity issues

- turnaround or operational improvements to ensure business sustainability.

The first step of the SOE Restructuring Project was to review existing processes relating to the FOPIP and restructuring plans based on two pilot companies, one from the manufacturing sector and the other from the transport sector. Each had followed one of these processes.

The next step was to draft two manuals – one for the Ministry and CERP and the other for SOE management – on preparing and implementing restructuring and FOPIPs, reflecting each stakeholder’s different role and responsibilities. Workshops were organised in 2019 with key stakeholders in the Ministry, CERP and the SOEs to gather feedback and test the proposed guidelines.

Regular reporting and monitoring of the liquidity of SOEs falls within the competence of SOE management, because management should be the first to know about any financial difficulties. The cornerstone of the SOE Restructuring Project Guidelines is an early warning system (EWS) for managing financially distressed SOEs.

Early action in relation to a distressed business is critical to minimise further financial losses and to give the company a real chance of successful restructuring and turnaround. Policymakers are increasingly emphasising the importance of early warning mechanisms to signal financial difficulties. The new Directive (EU) 2019/1023 requires member states to develop early warning tools to notify businesses in financial difficulty of the need to take prompt action.67

The EWS introduced by the Project uses a combination of internal and external indicators consisting of both qualitative and quantitative data to generate an EWS summary report. Internal indicators, such as the company’s debt ratio or liquidity ratio, are sourced from the new annual and mid-term reporting templates for SOEs, developed as part of a 2018 EU-funded project led by the EBRD and the SRSS. External indicators are split into local and global indicators for SOEs, including the general economic and political situation in Croatia and the global environment (Europe and the world). The EWS also incorporates a flagging system which identifies any changes in key performance indicators between different reporting periods.

If the report detects an early warning event, a process of closer monitoring by SOE management and the state bodies should begin. The Guidelines recommend the convocation of a so-called Early Action Committee, chaired and coordinated by either the Ministry or CERP as applicable and including persons from the relevant line ministries to oversee a particular SOE. The Early Action Committee may, depending on the financial condition of the relevant SOE, elect to start either a FOPIP or a restructuring plan. This triggers the beginning of a process illustrated in Chart 1. The Guidelines set out the basis on which SOEs nominated for either FOPIP or restructuring processes should prepare the FOPIP and/or restructuring plans and include examples of FOPIP and restructuring plan dashboards.

CHART 1: Dealing with financially distressed state-owned enterprises

Source: EBRD

Good corporate governance is critical to ensure timely and effective action. The Guidelines therefore emphasise corporate governance and proper management of the state ownership function in accordance with the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Guidelines on Corporate Governance of SOEs 2015.

Despite a move towards greater centralisation with the establishment of CERP and the Ministry, ownership of SOEs in Croatia is not fully centralised, as recommended by the OECD Guidelines. While the new 2018 Law on the Management of State Assets clarifies the overarching responsibilities of different state players, the Law does not address the granular split of specific tasks that each state body performs and how coordination between state bodies is to be achieved. The Ministry, for example, is responsible, in cooperation with other ministries and other state administration bodies and public entities, for proposing to the government a strategy for the management and disposal of state assets.

However, in practice the line ministries have greater influence over strategic decisions (such as approving SOE strategic plans and SOE restructuring plans and appointing SOE board members) than the Ministry and CERP. There is, furthermore, no existing, clearly defined state rationale or policy for its ownership of SOEs.

The SOE Restructuring Project Guidelines recommend that the Ministry or CERP (as applicable) play a driving role in any FOPIP or restructuring process. At the same time, the Guidelines stress, on the SOE management side, the responsibility of the supervisory board in leading the process and ensuring that SOEs deliver timely and comprehensive reports to the Ministry or CERP.

The Guidelines introduce a corporate red flag system to identify potential weaknesses that may reduce management accountability and the capacity of SOE boards to fulfil their responsibilities. They suggest that corporate governance red flags should be reviewed by the Early Action Committee following an EWS event, but state that red flags can also be used during normal times of operation.

One example of a corporate governance red flag is if the SOE supervisory board does not have a clearly defined and documented mandate and clear responsibility for overseeing management and guiding the enterprise’s performance.

Another example in relation to commercially oriented SOEs is any circumstance in which the relations of these SOEs with other SOEs (including state-owned financial institutions) or state agencies are not based on commercial grounds, potentially giving rise to a conflict of interest or connected transaction. Such transactions may reduce the profitability of SOEs and therefore contribute to their financial distress.

Where SOE management lacks skills, the Guidelines recommend considering the employment of a Chief Restructuring Officer to bring in valuable turnaround experience and skills and/or external advisers to guide SOE management.

Project achievements and lessons learned

Interestingly, while many SOEs are underperforming, there has been relatively little emphasis to date on improving internal early warning mechanisms and turnaround skills for SOEs, despite the fact that this could be an important interim step to any successful privatisation project.

In this article we suggest that SOEs should be more aware of available restructuring tools and of how to improve corporate governance management and processes to ensure that these are sufficiently rigorous to manage businesses going through financial difficulty. The Guidelines introduced as part of the Croatian SOE Restructuring Project may be useful for other economies where the EBRD invests and where SOEs continue to play a significant role in the economy.

In Croatia the Guidelines have laid the foundations for a more robust and coherent corporate governance structure for the state management of SOEs in financial distress. Workshops organised around the Project recommendations and the Guidelines have equipped the Ministry and CERP with the necessary knowledge and awareness to play more active roles as stakeholders. Nevertheless, key challenges will be to ensure the necessary level of internal cooperation given the existing decentralised management of SOEs through the Ministry of State Assets, CERP and the line ministries and bringing on board the necessary external specialist skills to implement a significant turnaround of underperforming SOEs.

Furthermore, at the state level there needs to be a comprehensive rationale for SOE ownership in order to improve operational efficiency and fiscal sustainability. Today, a number of SOEs in Croatia have a significant portfolio of non-operating assets, such as construction sites that have been out of use for decades despite potential interest for commercial use by the private sector. Such assets are no longer required in the day-to-day operations and do not currently generate general cash flow for the business. The EBRD is therefore planning to launch a new project in the first quarter of 2020 – in partnership with the SRSS – that would develop a framework for the Ministry to credibly record and categorise the non-operating assets in SOEs.